The African Development Bank estimates that Africa’s infrastructure finance needs total a huge USD130-USD170 billion a year, with a mammoth financing hole of between USD68 billion and USD108 billion.

There is no shortage of strategies aimed at filling this gap, from China’s Belt and Road Initiative, to the European Union’s (EU) Global Gateway and the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment.

(We heard at a recent event we co-hosted with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung on “Unlocking Africa’s Sustainable Infrastructure Potential” that indeed, the more initiatives the better).

But there’s a problem: you only have to scratch the surface of these initiatives, and ambitious objectives and spending targets give way to a shortage of bankable projects, difficulties in attracting private investors and a lack of domestic public finance. All hinder the impact and the scaling up of these initiatives.

Here, we review the teeming landscape of infrastructure initiatives in Africa and the challenges faced by investors and suggest ways of overcoming them.

Crucial infrastructure needs in Africa

Addressing Africa’s infrastructure is key to unlocking the continent’s economic prosperity. Sub-Saharan Africa still lags behind other regions on access to energy, water, and digital infrastructure.

In 2022, 600 million people—half of Africa’s population—still lacked access to electricity and 418 million people had no access to clean drinking water.

While roads are critical for the transport of passengers and goods, only 43 percent of Africa’s rural population has access to an all-season road and just 53 percent of roads on the continent are paved.

In terms of railway network, with an estimated density of 2.5 kilometre per 1000 square kilometres, Africa lies way below the global average (23 kilometre per 1000 square kilometres).

Table 1: Indicators on energy, water and digital infrastructure access, by region, 2020

| Indicator | Sub-Saharan Africa | South Asia | Middle East & North Africa | Latin America & Caribbean | Europe & Central Asia | North America | East Asia & Pacific |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to electricity (% of population) | 48.5 | 96.2 | 97.2 | 98.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 97.8 |

| People using at least basic drinking water services (% of population) | 63.4 | 92.1 | 94.2 | 97.1 | 97.8 | 99.8 | 95.2 |

| Fixed broadband subscriptions (per 100 people) | 0.6 | 2.1 | 10.6 | 14.9 | 30.0 | 36.6 | 26.5 |

Source: World Bank Development Indicators.

A proliferation of initiatives

China was first on the scene in 2013 with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an ambitious plan to connect Asia with Africa and Europe through land and maritime networks.

For close to a decade, China occupied the centre stage in infrastructure financing around the world, with an estimated disbursement of over USD one trillion, with another USD100 billion pledged at the BRI 10th anniversary.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU and the G7 have ramped up their ambitions to reinvest in global infrastructure and challenge China’s dominance.

In late 2021, the EU launched the Global Gateway as a EUR300 billion alternative to the BRI, with half of this amount earmarked for Africa.

In 2022, G7 leaders formally launched the USD600 billion Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), which builds on the Global Gateway and the commitment of the United States to mobilise USD200 billion.

The United Kingdom pledged to mobilise USD40 billion while Japan pledged USD65 billion.

What sets the BRI apart from these initiatives is scale, and also speed. Because of the fusion between the public and private sectors in China and the fact that most of the private investors are either provincial or state-owned enterprises, it has been able to move significantly faster than the other initiatives.

Private sector investment is key: to achieve scale, there must be a substantive and material increase in private sector investment.

Outside of the G7, other countries established their own infrastructure plans. Over the last few years, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, have all expanded their investments in overseas infrastructure, with a clear focus on Africa.

Different plans, similar challenges

Although these global infrastructure plans differ in terms of objectives and scale, they all face a similar set of challenges in their ambition to close the substantial financing gap.

Firstly, there is a chasm between the capital available, and the number of bankable projects. World Bank analysis has shown that despite an annual investment need of USD2.6 trillion, the pipeline of greenfield projects in emerging markets and developing economies is estimated at just USD1.2 trillion.

The Global Infrastructure Facility, a G20 initiative to build bankable projects through the provision of advisory services and project preparation approved just USD19 million for 25 project activities in 2022.

Secondly, as previously pointed out, the success of the initiatives relies on mobilising private sector investment.

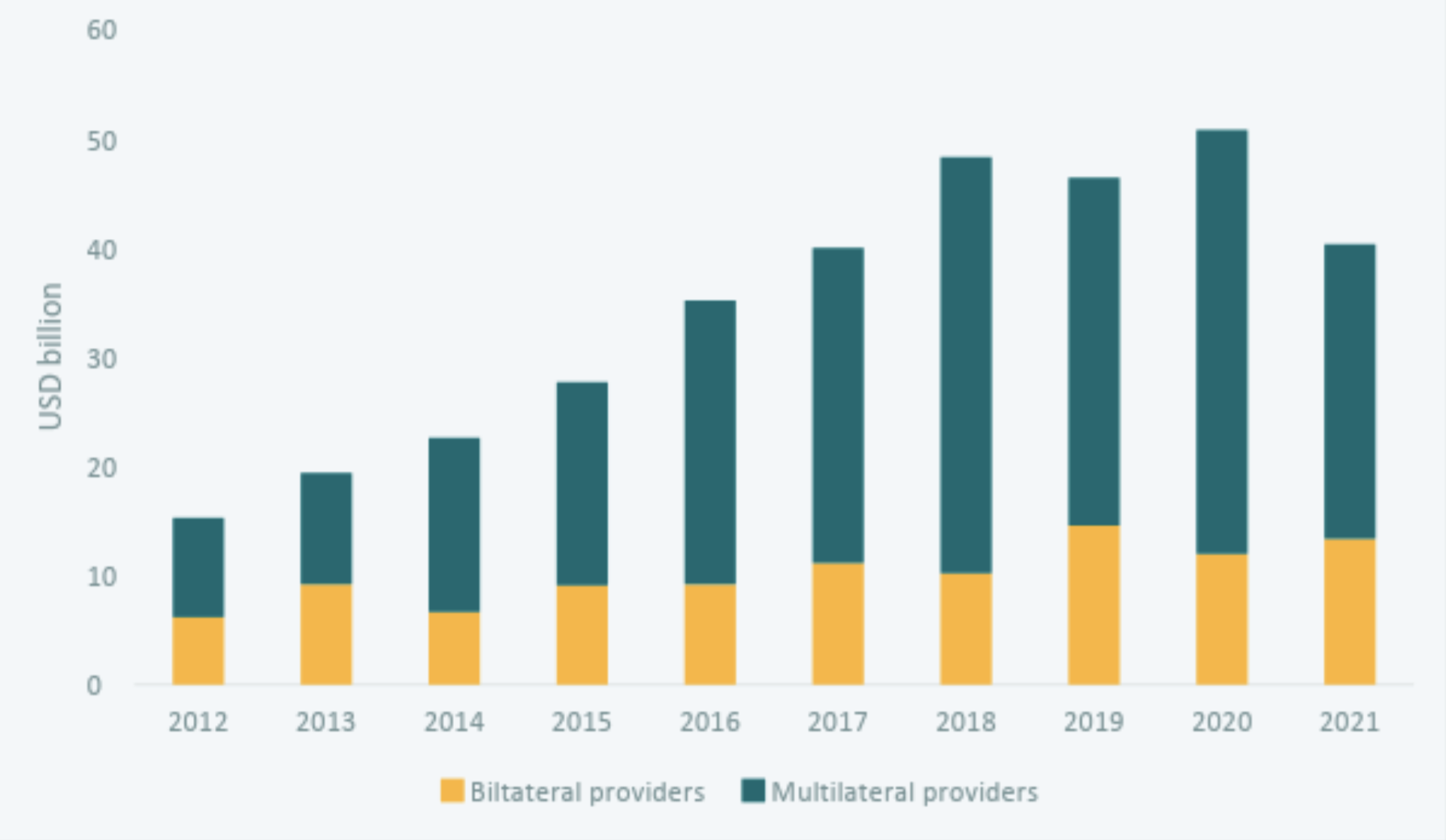

However, this has yet to materialise. According to the OECD, following three years of relative stagnation, private finance mobilised for sustainable development in 2021 has considerably decreased. (see figure 1). Moreover, mobilised private finance by bilateral providers has remained relatively stable over the last decade at around USD10 billion.

Figure 1: Mobilised private finance by bilateral and multilateral providers, USD billion 2012-2021

Source: OECD.

Thirdly, infrastructure investments often occur with little to no domestic participation. In Africa, domestic resource mobilisation remains weak. Average tax-to-GDP ratio in Africa (based on 33 countries) was estimated at 15.6 percent in 2021, lagging other developing regions, stymieing efforts towards reducing the financing gap for infrastructure.

Overcoming the challenges

Project preparation and support

A dearth of bankable projects—projects that meet the stringent requirements of financiers—remains a key bottleneck to investment in developing countries.

But not enough financial resources are being dedicated to developing strong feasibility studies, analysing market prospects and developing viable business plans, which results in many projects being rejected.

Neither the Global Gateway nor the PGII have dedicated plans for project preparation.

We have previously proposed the creation of an Accelerator Hub—a single access point for targeted support to identify, prepare and develop investment projects.

Private sector mobilisation

While there has been innovation in mobilisation structures and processes, the required step change in mobilisation volumes is yet to materialise, The USD40 billion of private finance mobilised in 2021 by both bilateral and multilateral providers made only a modest contribution to filling financing gaps.

In a CGD policy paper, colleagues set out a series of recommendations for expanding the use of the innovations that have proved successful in addressing mobilisation constraints.

Furthermore, as part of the MDB Reform Accelerator, a hub for evidence-based analysis and strategic outreach around MDB reform, CGD launched a series of conversations with experts in both private and public funding sharing their insights on the changes needed to increase the mobilisation of the private sector.

In these conversations, stakeholders called for the expansion of the use of instruments such as partial credit guarantees and the revision of capital requirements for commercial banks in order to attract additional private investments.

Domestic resource mobilisation

Although some progress has been made in mobilising tax revenue, too many countries still rely on poorly designed tax systems that are blocked from reform by institutional barriers. An IMF paper finds that a combination of better tax design and capacity building can substantially increase tax revenues, unlocking critical resources for development and climate investment.

And CGD colleagues have recommended the Multilateral Development Banks to use an outcome-based payment system, in which concessional lending matches half of a 1 percentage point increase in tax revenue to GDP ratio to create incentives for countries to implement reforms to increase tax revenues.

The scale and scope of Africa’s infrastructure challenges are beyond that which any one partner can provide.

Today, despite the proliferation of infrastructure initiatives with a strong focus on the African continent, there continues to be a substantial financing gap. Mobilising additional public and private finance domestically and internationally in the coming years will be key to closing the gap.

The success of these grand initiatives rests on overcoming the bottlenecks in the preparation of bankable projects, the capacity to attract private investors and the ability to raise domestic revenues.

Courtesy: Centre for Global Development

Also Read

South Africa Infrastructure: Prevention is better than cure

Mining industry urged to invest in ‘disruptive’ digital technology to add value

- South Africa Fuel Restrictions Are Squeezing Construction Sites — Here’s What Contractors Need to Know - March 13, 2026

- The $104 Billion Question: Why Africa’s Hotel Pipeline Keeps Missing Opening Deadlines - March 12, 2026

- What FlySafair’s First-Ever Fuel Surcharge Tells Us About Construction Costs Ahead - March 12, 2026